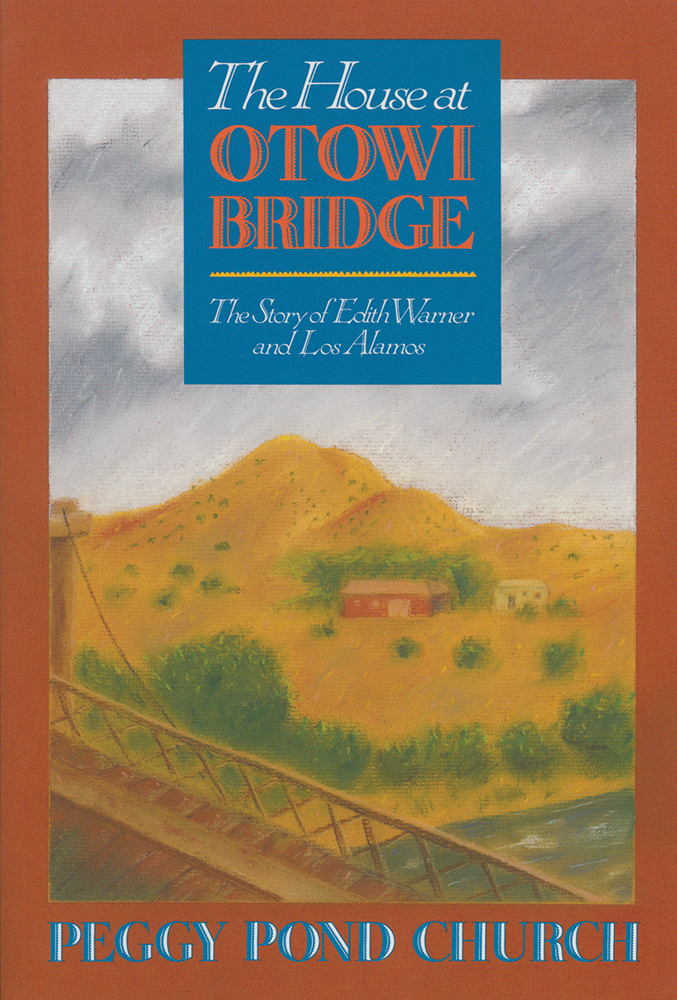

The House at Otowi Bridge: The Story of Edith Warner and Los Alamos, by Peggy Pond Church absorbed me from the start. The author had grown up in the area and lived at Los Alamos for some twenty years before the U.S. government took it over as a location for nuclear research. She was also a poet, and the book has a sweetly descriptive nature to the writing, with a warm, personal tone to it. It’s really the story of both the writer and her subject.

Edith Warner settled in the area in the 1920s, when she was in her thirties, and lived there for the rest of her life, until after the war. Warner was from Pennsylvania and went to the dry climate of New Mexico for her health, as so many people did. She fell in love with the vistas, the tranquility, and the Indians of San Ildefonso (also famed for its black pottery created by Maria Martinez) while she stayed at a guest ranch. She wanted to remain in the area but finding a way to earn a living was almost impossible. When she was offered a job living in a small cabin next to a railway crossing, where she would be responsible to the care of whatever was unloaded on the daily train, it seemed an unlikely job but it was the only choice and she took it.

She fixed up the cabin in simple ways, with the help of Indians whose land it was on, and she lived there. She could hear the nearby Rio Grande and feel the tranquillity of such a remote spot, a few miles from the nearest pueblo. She kept tea and coffee ready to serve to visitors, and over time became known for having a chocolate cake recipe which nobody could duplicate. She started a tearoom as another source of income.

She was uneasy alone at night but someone gave her a revolver and she learned the basics of using it. Word had spread through the countryside that she was there alone. One night, when a man crept close to the house, she shot into the air. He ran to his horse and galloped away. Then word spread about the revolver and she had no more unwanted visitors.

She was naturally a quiet person and didn’t plague the Indians with questions the way so many white people did. Within a few years, many of them had become her friends, whether or not they had a language in common. The Indians spoke Tewa and some Spanish and English; she learned a little Tewa.

Tilano, an Indian man about twenty years her senior, came to live with her. He had his own room and it’s not evident if they were partners in the way we would think of. He cut wood for the fireplace he had built in the cabin, milked her cow, and kept busy with other heavy work. He was unusual in that he had gone to Europe years before in a group of Indian dancers, so he had a broader perspective. His wife had died. He was there for the rest of Warner’s life, until he was past eighty. Along with income from the train work and the tearoom, they built a small adobe cabin which Warner rented out to other white people who needed a quiet retreat.

Early in the 1940s the little railroad line was discontinued and the road was improved. The school up on the mesa where Peggy Pond Church’s husband had taught was claimed by the government and Los Alamos became the site of nuclear research. Hundreds and then thousands of people moved up there.

Warner’s life changed dramatically. She had met Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the project, years earlier. He started going down to Otowi Crossing as a break from his work. Warner cooked meals for him and his wife, and that developed into cooking for many of the scientists who needed to relax without taking the long drive to Santa Fe. It was a very busy time for her and Tilano.

The book ends with the story of Edith Warner’s passing, her famous chocolate cake recipe, the Christmas letters she had been writing, and poems of Peggy Pond Church. I hated to finish the book. But it was an excellent precursor to another book in my pile, one about the scientists at Los Alamos. And it framed my own experiences of New Mexico in a way that nothing else could have.

It left me with a feeling of poignancy. She had lived in a peaceful manner that goes back centuries, while up the hill at Los Alamos the bomb being invented would change life on earth forever.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rosana Hart was a toddler at Los Alamos during the war, when her father was fighting in China. Her mother’s father, Chester Snow, was a mathematical physicist who went to Los Alamos to work on the bomb in the early 1940s. He took his wife, his daughter Margaret, and the granddaughter who now writes as Zana Hart. Zana’s earliest memories are from Los Alamos. She has been reading about these long-ago years as she works on a memoir from that era. It’s called Science Fiction Daughter, as her father wrote science fiction under the pen name of Cordwainer Smith.